How do states turn public health messaging into real behavior change and how do the places we live shape our health every day? In this episode, Dr. Steven Stack, secretary of Kentucky’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services, discusses the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign and what it takes to move beyond awareness to action. Dr. Stack, an ASTHO member and former ASTHO president, shares how Kentucky is using simple, achievable goals—eat healthier, move more, and stay socially connected—along with clear calls to action, trusted partners, and data-driven refinements to engage residents and build long-term, sustainable health improvements. Then, Clint Grant, director of healthy community design, chronic disease, and health improvement at ASTHO joins us to explore the growing role of healthy community design in public health. From transportation and road safety to green space and mobility, Grant explains how decisions about streets, sidewalks, and transit are some of the most powerful, and often overlooked, public health choices states and communities make.

How do states turn public health messaging into real behavior change and how do the places we live shape our health every day? In this episode, Dr. Steven Stack, secretary of Kentucky’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services, discusses the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign and what it takes to move beyond awareness to action. Dr. Stack, an ASTHO member and former ASTHO president, shares how Kentucky is using simple, achievable goals—eat healthier, move more, and stay socially connected—along with clear calls to action, trusted partners, and data-driven refinements to engage residents and build long-term, sustainable health improvements. Then, Clint Grant, director of healthy community design, chronic disease, and health improvement at ASTHO joins us to explore the growing role of healthy community design in public health. From transportation and road safety to green space and mobility, Grant explains how decisions about streets, sidewalks, and transit are some of the most powerful, and often overlooked, public health choices states and communities make.

States Invest in Public Health and Safety Through Transportation Policy | ASTHO

Key Insights to Improve Infection Prevention in Dialysis Settings | ASTHO

Our Healthy Kentucky Home | KY Cabinet for Health and Family Services

JOHN SHEEHAN:

This is Public Health Review Morning Edition for Wednesday, January 21, 2026. I'm John Sheehan for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

Today: how states turn public health messaging into real behavior change. We'll hear from Dr. Steven Stack, Secretary of Kentucky's Cabinet for Health and Family Services, about the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign. Dr Stack is an ASTHO member and former ASTHO president, and will share how Kentucky is using simple, achievable goals with clear calls to action to build long-term, sustainable health improvements. Later, we'll hear about healthy community design and public health from Clint Grant, ASTHO's director of healthy community design, chronic disease, and health improvement. From transportation and road safety to green space and mobility, Clint will explain how decisions about streets, sidewalks, and transit are some of the most powerful and often overlooked public health choices states and communities make.

But first, Dr Steven Stack. I asked him about the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign, which by late last year, had racked up 28,000 website visits and 54 million social media hits. I wanted to know if that was translating to behavioral changes in Kentucky.

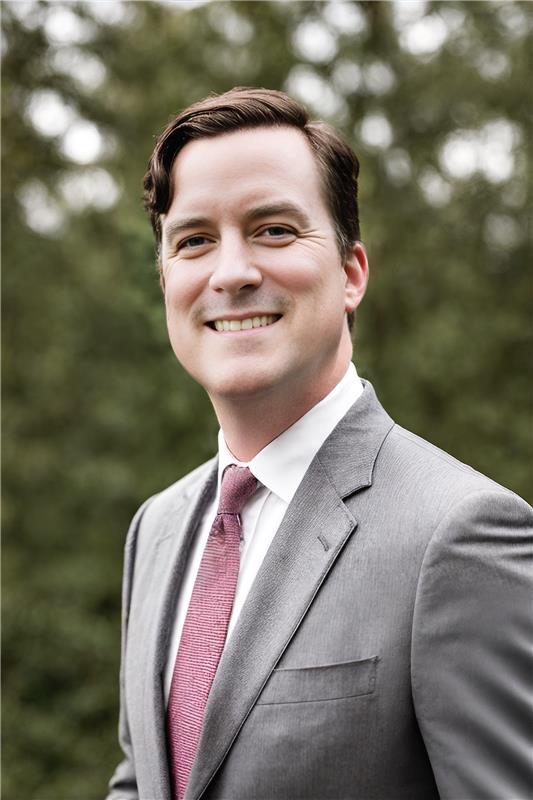

STEVEN STACK:

So, the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign is an attempt to have simple, actionable steps people can take to lead healthier, happier lives. So of course, trying to change and improve the health of four and a half million Kentuckians is no small undertaking. But we do look for signs of engagement. We have good traffic on our website and social media posts. We're monitoring increases in participation in our programs, the services that we refer people to. We're looking at resource downloads, time spent on health topic pages on our website, hotline calls. We're trying to see if we're getting increased engagement for people calling our phone numbers, and click-through rates on seeking services on our online and social media links. And then we're getting feedback from partners, and we are seeing a number of partners who are trying to incorporate the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' campaign and its themes into their own work and creating derivative products. So a variety of ways we look for this but, but of course, it's, it's imperfect,

SHEEHAN:

And this is year two of the initiative. Do you see the need to adjust your approach, or are you staying the course?

STACK:

Well, yes, both. So, part of it is staying the course. So it's eat, exercise, and engage. That's the shortest way to say the foundation of the campaign. More detail is eat at least two servings or fruits or vegetables every day, exercise at least 30 minutes, three times per week, and remain socially engaged, to be socially connected. And so those things are really foundational, and they're also modest. That's not the number of fruits and vegetables or the minutes of exercise that are national guidelines, but we know from our own data, our own surveys in the state, that people are so far from reaching those national guidelines that we need to make the initial goals more attainable, and so we're going to continue to emphasize that in the whole second year. And if we do a third year, we'll do it in the third year, because the goal is to try to get the folks who are doing the least to start doing more, not to get the people already doing lots, to do even more beyond that. But then we're also going to focus. We learned from the first year, the posts that we made on social media that got the most circulation were very concrete, resource based posts when we gave people a call to action, a phone number, they could call a website, they could visit a place, they could go to get resources or help. Those were shared, and people, hopefully, therefore, were making better use of that.

SHEEHAN:

Yeah. What are some other examples of strategies for residents that you're using to sort of get those resources out there?

STACK:

So, we work real hard to make sure that the website provides really clear and plain language breaks things down into short steps that lead directly to resources, or programs, or tools that we offer. The social media posts links straight to the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' website, and we try to drive everything to the 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' website as much as possible. So it's a central hub. We do use a variety of short videos to try to engage people's attention and break it down into just a couple minutes of digestible information, and we continue to use the same core themes over and over, I think we underestimate sometimes that it requires a lot of repetition for a simple Message to get through the noise and chaos of all the things we're exposed to, social media and other communication channels.

SHEEHAN:

Sure, given that it's only year two, do you think you have lessons learned that might be helpful for other health agencies?

STACK:

Yeah, so for other states you might want to do this, we'd say, keep navigation simple. Reduce steps for people to engage resources wherever possible, use trusted local partners, our residents, our citizens, rely on familiar faces to have trust and confidence in the information. Track what pathways people use and refine quickly. If you're learning that certain types of posts or certain avenues of sharing are better taken up by your population, then highlight those and. Diminish the other ones, and awareness alone isn't enough. People need a clear, easy next step and a trusted outlet to learn more. So be concrete and point them somewhere where they can take action themselves. Make it as simple as possible. I think those things help improve the likelihood of uptake.

SHEEHAN:

Each month has been around a different theme in the program, how do you track if those thematic elements are working?

STACK:

Sure, so we track theme specific web visits, downloads and time spent on the resources we provide. We monitor our social engagement tied to each month's topics, and we can see which posts really take off much more than others, and then try to give more of the type of content that resonated with people. We try to collect partner reports from local events or screenings or community outreach efforts that they do that align with these themes, and hear what they're doing on the ground from our local partners. We also review referral and program utilization data to see if more Kentuckians are perhaps accessing resources. So, if we highlight tobacco cessation resources, or we highlight diabetes prevention resources, or we highlight food insecurity resources, do we see an uptick in calls to our call lines or website access, and then we're trying to plan for long term growth so that we can build out those programs where we have the resources that people most need and want in order to provide for meaningful support for meaningful health change over time, because it takes time and consistency to achieve better population health that's durable.

SHEEHAN:

Yeah, absolutely. Talk a little more about how you plan for making a sustained, long-term approach like this, and what other states could learn?

STACK:

Well, I think 'Our Healthy Kentucky Home' aligns with Governor Beshear's overall message of 'Our New Kentucky Home,' and so, it is intentionally harmonizing, so that those reinforce in the messages the goals I've mentioned before is very simple, eat healthier, exercise more, and be socially engaged and meaningfully socially engaged, not on smartphones or other technology devices, in person with people, which really is a much more engaging and fulfilling experience, and then staying consistent with that over a longer period of time. So we've already done one full year. This is the second year, and the governor's got almost a third year left in his term, and so hopefully we'll continue this over a longer arc and see if we can't drive change and make this more ingrained in our thoughts and our behaviors and meet people where they are.

SHEEHAN:

Dr. Steven Stack is secretary of Kentucky's Cabinet for Health and Family Services, an ASTHO member, and former ASTHO president.

Now for a different perspective on influencing population health and behavior, let's go to Clint Grant, director of healthy community design, chronic disease, and health improvement at ASTHO. I wanted to know what was meant by 'healthy community design.'

CLINT GRANT:

At its core, healthy community design recognizes that health isn't created in a doctor's office or hospital. It's really shaped by the environments we move through every day. You know, the way I look at healthy community design is that it brings together public health and transportation, for example, as well as community voices to ensure our communities are livable, safe, as well as accessible. You know, one of the great things about healthy community design is states can play a critical role here when it comes to helping to set design standards and policies and funding priorities that can really shape how our communities look for generations.

SHEEHAN:

Yeah, and there's a lot to unpack there. I feel like you touched on not just sort of infrastructure, but the way communities are laid out, green space, the existence of power lines, all these kind of things that maybe you don't think of on your day-to-day, but they do, they do factor into how a community is planned and the health of its residents.

GRANT:

Yeah, absolutely. So, you know, just the simple presence of a park space has shown to improve mental health conditions for community members. You know, the existence of barriers such as roadways or power lines, as you mentioned, that can restrict movement and freedom of movement also goes a long ways to whether or not communities and individuals are able to safely be physically active or want to be physically active and connecting with one another. The pandemic really showed that the impacts of social isolation and how we develop our communities can really play a big role in in this sense that someone has with being connected to their community, whatever that may look like.

SHEEHAN:

And today we're talking specifically about transportation. Can you connect the dots for us between transport? Transportation infrastructure, or, you know, access to transportation and how that connects to public health?

GRANT:

Yeah, absolutely. So, transportation decisions are some of the most powerful and often overlooked public health decisions that we make. Transportation can impact the risk of injury. You know, whether or not an individual is physically active, are the air we breathe, the water we drink, whether or not we have access to care, or to jobs or economic opportunity, and even social connection. And so, when we're looking specifically at transportation, you know, spaces like our streets, whether or not they have sidewalks, our school zones. You know, are they at a safe speed? You know your transit stops, your bus stops, you know Metro access, they all influence whether people feel safe being active. And as a parent, whether or not, you know I'm comfortable letting my kids walk or bike to school. So, when it comes to road safety, states are really starting to focus on vulnerable road users, which are your pedestrians, and cyclists, and people with disabilities, children, older adults. And this is really exciting, because vulnerable road users face much higher risk because they're they have less physical protection as well as visibility on the roadway, which is why there's been an epidemic of sorts of serious injury and death related to traffic incidences.

SHEEHAN:

Yeah, 100% and there's so much complexity there, from not just sort of access to modes of transportation, but also, you know, increasingly lanes for electric scooters or electric bikes, or shared bikes, or just bicycles in general. I know a lot of cities are sort of taking that up, but, you know, the infrastructure originally just wasn't designed for it. So there's a, there's a big hill to climb there.

GRANT:

Yeah, absolutely, when we're looking at shared use, that's a tremendous area of growth over the past decade, plus looking at reimagining our streets for being for people, not just for cars. You know, also we look at the cost of owning a motor vehicle, owning a personal car, those costs continue to grow. So there's an equity piece to it as well. And if we're making decisions that are strictly based off of the availability of a personal vehicle, we're cutting out opportunity for so many others.

SHEEHAN:

Yeah, these are all choices we're making, whether to put it, to add a parking space or to add a sidewalk, whether to create a green that is no vehicles, or to add another, you know, access point. Communities make those decisions.

GRANT:

Yeah, yeah. Communities absolutely make those decisions, and they have a voice to be able to speak up. And you know, that's one of the great things about many of the planners that I engage with and have talked with over the years, whether it's your municipal planners or state-based planners or folks in nonprofits, the voice of the community is very important. And as public health practitioners, oftentimes we are, you know, we go to these quote, unquote tables where these planning decisions are made. And it's really important that we bring the data to be able to support decisions that may not be popular. You know, when we look at adding a additional lane of traffic, you know, adding, you know, one more lane to an interstate or a highway on the efficiency scale, that ranks very high, but when we look at the health impacts, there are clear impacts, and that's where public health professionals can come in to really elevate that and highlight that point.

SHEEHAN:

What advice would you have for state officials that you know see this need in their communities that want to get involved in in those kind of planning decisions?

GRANT:

The advice I would, I would give, is, be yourself. Be a public health professional. Don't try to be a transportation engineer, or urban planner, or rural planner. Stick to what you know and be able to speak in a sense that conveys that message, whether you know, as public health professionals. We may be stepping in as the person that advocates for community in public health. We are fantastic conveners. We are asked to be chief health strategist all the time, and so, use that, that ability and lean into it. Be able to pull different groups together, if there are any plans that are, you know, being discussed, if there are community events, you know, take 10-15, minutes out of your day to go in to listen and learn from what the planners are saying. Well, also, the community is saying, and then bring your public health knowledge to the table and be, be willing to speak up for the public that we love and serve.

SHEEHAN:

Are there any examples from states that are doing anything innovative or different or that have had particular successes?

GRANT:

So, there are a couple of states that come to mind, first being California. So, California recently put in place a policy that lowers school zone speed limits to 20 miles per hour. It may not sound like a lot, but that's actually a pretty huge accomplishment, because it's creating safer environments for, once again, our vulnerable road users, our children. This also has a ripple effect of reducing the need for school buses. You know, Hawaii, they've adopted a policy recently that addresses intersection daylighting, so these walls focus on parked cars near crosswalks. We know that if a car is parked directly in front of a crosswalk, it's limited visibility of pedestrians, and a lot of our conflicts between pedestrians and motor vehicles are at intersections, and one of the really neat things that they're also doing is if, if they find a car that is in violation of this new law, those funds are being directly sent to the Safe Routes to School program. Another strong example is New Jersey's Target Zero commission. This Commission's working towards eliminating all traffic fatalities and serious injury by 2040 it's going to be a hard goal, but it's a goal that's definitely doable. And by pulling together different industries, transportation, public health, community based organizations, nonprofits, advocacy groups, by pulling all these folks together, you're getting diverse thoughts, different opinions on how to address this issue that's I'm really excited to watch over the next few years as they continue to grow.

SHEEHAN:

Clint Grant is ASTHO's director of healthy community design, chronic disease, and health improvement. Earlier, we heard from Dr. Steven Stack, secretary of Kentucky's Cabinet for Health and Family Services, and ASTHO member and former ASTHO president.

Dialysis-related infections remain a serious and preventable threat to patient safety. Each year, 1000s of patients experience bloodstream infections that can lead to hospitalization or worse. New insights from CDC's Making Dialysis Safer for Patients Coalition highlight what works; creating a strong culture of safety, empowering frontline staff with practical role, specific training, and ensuring visible, engaged leadership. Health Departments play a critical role in bringing these strategies to life through collaboration technical assistance and support for dialysis facilities nationwide, learn more and visit the link in the show notes.

Public health data is evolving and interoperability is the next frontier. Join us, Thursday, January 22, for a webinar, 'The next frontier of public health interoperability: TEFCA, HDUs, and what comes next.' Experts from state and local public health, health information exchanges, and data networks will explore how intermediaries like HIEs, and health data utilities are making real-world data exchange possible, and what it means for public health action.

This has been Public Health Review Morning Edition. I'm John Sheehan for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.